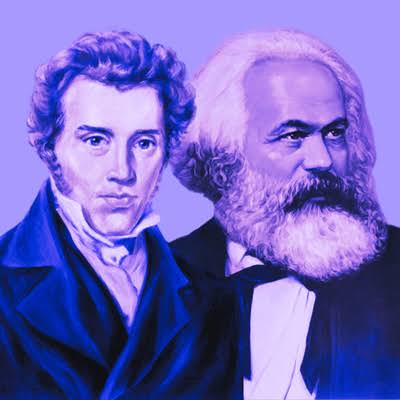

We have often used this statement by Marx to attack others:

“Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. Caussidière for Danton, Louis Blanc for Robespierre, the Montagne of 1848 to 1851 for the Montagne of 1793 to 1795, the nephew for the uncle.”

It is time to use it to critique ourselves, as we too have our Lenins, Trotskys, Stalins, Maos, Ches….

Actually, the whole first chapter of The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte is a necessary reading to understand and critique the left and also its obsession not so much with history but with historical facts.

Marx’ critique of revolutionary language in that chapter is quite powerful. (We should perhaps also keep in mind that when Marx was writing this text the French Revolution had happened around 60 years ago. But for us the Russian Revolution happened more than 100 years ago, the Chinese Revolution 70 years ago and…)

Another famous quote from the text is “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”

This is generally posed as a principle of historical materialism, to counter idealism and voluntarism. But Marx uttered this to critique ideology —the process of the fetishisation of the past —names, slogans and costumes etc.

What immediately follows the above statements is quite revealing. It shows how and why such fetishisation happens and ideologies are formed:

“The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language.”

He adds,

“Thus Luther put on the mask of the Apostle Paul, the Revolution of 1789-1814 draped itself alternately in the guise of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and the Revolution of 1848 knew nothing better to do than to parody, now 1789, now the revolutionary tradition of 1793-95.”

We can easily replace these figures and facts with ourselves and the historical names, costumes etc with which we seek to connect to.

In fact, Marx compares this tendency with that of “the beginner who has learned a new language”. He “always translates it back into his mother tongue.” But “he assimilates the spirit of the new language and expresses himself freely in it only when he moves in it without recalling the old and when he forgets his native tongue.”

So in which stage of learning are we presently?

Marx differentiates between those who were indulging in “conjuring up of the dead of world history” during his own time and the old French revolutionaries. The latter “performed the task of their time – that of unchaining and establishing modern bourgeois society – in Roman costumes and with Roman phrases.” Once the tasks were completed, the “resurrected Romanism” also disappeared.

According to Marx, the bourgeois revolutionaries needed the old language of “heroism, sacrifice, terror, civil war, and national wars” to bring the bourgeois society into being, as it was in itself unheroic. “And in the austere classical traditions of the Roman Republic the bourgeois gladiators found the ideals and the art forms, the self-deceptions, that they needed to conceal from themselves the bourgeois-limited content of their struggles and to keep their passion on the high plane of great historic tragedy.”

But what is our purpose in conjuring the past?

Marx further says:

“Thus the awakening of the dead in those revolutions served the purpose of glorifying the new struggles, not of parodying the old; of magnifying the given task in the imagination, not recoiling from its solution in reality; of finding once more the spirit of revolution, not making its ghost walk again.”

But during Marx’s time, as in our times too, “only the ghost of the old revolution circulated”. The old names, facts etc become means to disguise, and hide trivialities and “repulsive features”. Only “caricatures” could be produced now with these. Why is this so? Because,

“The social revolution of the nineteenth century cannot take its poetry from the past but only from the future. It cannot begin with itself before it has stripped away all superstition about the past. The former revolutions required recollections of past world history in order to smother their own content. The revolution of the nineteenth century must let the dead bury their dead in order to arrive at its own content. There the phrase went beyond the content – here the content goes beyond the phrase.”

So, what lessons can we draw from all this? For this purpose, let us improvise on the last quote.

Today, “the social revolution… cannot take its poetry from the past but only from the future. It cannot begin with itself before it has stripped away all superstition about the past.” Let us not use “recollections of past world history in order to smother” the content of today’s revolution.

Today, “the revolution… must let the dead bury their dead in order to arrive at its own content.” We must not allow our phrases to overpower and hide the content, since the content today will tear every veil of phraseology.

Didn’t Lenin too tell us not to behave like comedians who “chase words, without thinking about how devilishly complicated and subtle life is, producing entirely new forms, which we only partly ‘catch on’ to”? We must go beyond words and phrases, beyond our literary preferences of names and facts.