सम्पादकीय (ड्राफ्ट), मोर्चा

उनका तर्क है कि कोई भी चीज़ स्वयं को केवल एक ही प्रकार की चीज़ के रूप में दोहरा सकती है, तथा किसी भिन्न चीज़ में परिवर्तित नहीं हो सकती। — माओ

“विश्व इतिहास में… सभी अत्यंत महत्वपूर्ण घटनाएं और हस्तियां… दो बार आविर्भूत हुई हैं।… पहली बार दुखांत नाटक के रूप में और दूसरी बार प्रहसन के रूप में।” मगर ये घटनाएं यथार्थ में दो बार नहीं होतीं, बल्कि अतीत की मृतात्माएं भाषा, परंपरा, नाम, रणनाद और परिधान मुहैय्या कराती हैं जिन्हें उचित संप्रेषण के अभाव में “विश्व इतिहास की नवीन रंगभूमि को इस चिरप्रतिष्ठित वेश में और इस मंगनी की भाषा में सजाया” जाता है। मार्क्स के अनुसार, इस “भोंडी नकल” से प्रगतिशील ताकतें भी अछूती नहीं होती।

प्रतिक्रियावादी ताकतें स्वभावतः राष्ट्रवादी, नस्लवादी, जातिवादी अतीत के “गौरव” को पुनश्च जीती हैं, मगर अपने आप को सर्वहारा क्रांति के हिरावल मानने वाले यदि अतीत को जीने लगें तो समस्या है। अतीत की समझ जरूरी है (यह मार्क्सवादी से अधिक कौन जानता है) मगर उनमें संदर्भ के ऐसे बिंदुओं की तलाश करने के लिए, जो हमें वर्तमान में हमारे स्थान को स्थापित करने में मदद करें, ठीक उसी तरह जिस तरह नाविकों को आकाश के तारे मदद करते हैं। जब वर्तमान का अर्थ धूमिल हो रहा हो तो अतीत के वे बिंदु हमारे लिए तारों का काम करते हैं। मगर आज की सामाजिक क्रांति अपना काव्य अतीत से कभी नहीं गढ़ सकती, उसे भविष्य से ही गढ़ना होगा। बेगमपुरा की नगरी अतीत में नहीं है, भविष्य में है।

इतिहास और वर्तमान की समझदारी का रिश्ता एकतरफा नहीं होता यानी इतिहास पर आपकी पकड़ वर्तमान में आपको शातिर बना देगी, ऐसा बिल्कुल नहीं है। ज्यादा समय इतिहास के ज्ञान का बोझ आपको ऐतिहासिक रूपकों की भूलभुलैया में विलीन कर देता है, और वे मिथक का काम करते हैं। तथाकथित वस्तुनिष्ठ इतिहास के प्रचारक वर्तमान को महज उसका निष्कर्ष मानते हैं, जबकि गतिशील वर्तमान हमेशा नया इतिहास रचता है, उसमें नए बिंदुओं को तलाशता है ताकि भविष्य के रास्तों को ढूँढ़ सके। इतिहास का विकासवादी (evolutionary) दृष्टिकोण, वर्तमान की नवीनता को नहीं स्वीकारता, वह स्वरूपात्मक पुनरावृत्तियों की भाषा में उसको बांधने का प्रयास करता है। वर्तमान का हरेक नया क्षण इतिहास के पुनरावलोकन के लिए अवसर प्रदान करता है — पुराने क्षणों को देखने और समझने के लिए नया दृष्टिकोण देता है। इसके विपरीत, नए में पुराने को खोजने की जिद्द में इतिहास के दरारों और छलाँगों को नजरअंदाज करने से हमारी राजनीति और हमारे संघर्ष निश्चित व्यवस्थापरक सीमाओं में बंधे रहते हैं, जबकि संघर्षों में हमेशा अंतर्निहित अमूर्त संभावनाएं होती है, जो संयोगों की जननी हैं जिनसे इतिहास की गति में छलांग पैदा होती हैं।

फासीवाद के ऐतिहासिक रूपक से वर्तमान के दक्षिणपंथी उभार की समझदारी को प्रस्तुत करने में अवश्य ही मदद मिलती है, परंतु जैसा कि अलेक्जेंडर रोसेनब्लूएथ और नॉर्बर्ट वीनर ने लिखा है, “रूपक की कीमत शाश्वत सतर्कता है।” जीव-वैज्ञानिक रिचर्ड लेवॉन्टिन “द ट्रिपल हेलिक्स” में इस बात पर टिप्पणी करते हुए कहते हैं — प्रकृति के बारे में बात करते हुए हम रूपकों के उपयोग से बच नहीं सकते, लेकिन रुपक को वास्तविकता के साथ घालमेल करने का खतरा हमेशा बना रहता है। हम दुनिया को मशीन की तरह से देखना बंद कर, मशीन ही समझ बैठते हैं। प्राकृतिक विज्ञान के क्षेत्र से कहीं अधिक यह समाज और सामाजिक विज्ञान के क्षेत्रों में होता है। सामाजिक अवधारणाएं, खास तौर से जो मूर्त तौर पर किसी ऐतिहासिक काल, घटना इत्यादि से जुड़ी होती हैं उनका इस्तेमाल वर्तमान के चित्रण और समझ के लिए अनिवार्य हैं, परंतु उन्हें उनकी ऐतिहासिकता से काट कर भौतिकवैज्ञानिक अवधारणाओं की तरह इस्तेमाल नहीं किया जा सकता। फासीवाद की मूर्तता जो इटली और जर्मनी या फिर उस समय के अन्य धुर–दक्षिणपंथी आंदोलनों में मिलती है, उसे इन आंदोलनों या उनके समय के इतिहास से निकालकर उनका अवधारणात्मक इस्तेमाल करना खतरनाक है — क्योंकि इससे उनके खिलाफ की लड़ाई की “भोंडी नकल” का खतरा पैदा हो जाता है।

पिछले कुछ अंकों से हम घोर दक्षिणपंथी आंदोलनों, राजनीति और सत्ताओं के उभार की जांच हेतु सामग्रियों का प्रकाशन कर रहे हैं। इन सामग्रियों और चर्चाओं ने इतना तो साफ किया है कि उस जमाने के फासीवाद और नाजीवाद जिस रूप में सामाजिक उत्कंठाओं और कुंठाओं की उपज और अभिव्यक्तियाँ थे, आज के धुरदक्षिणपंथ भी उसी तरह आज की उत्कंठाओं और कुंठाओं की उपज और अभिव्यक्ति हैं। उनके तौर-तरीके में भी समानता दिखती है। परन्तु विद्यमान नव-उदारवादी पूंजीवादी चरण की विशेषताएं इन राजनीतिक अभिव्यक्तियों की भूमिकाओं और कार्यकलापों को नया स्वरूप और नया अर्थ देती हैं। आज के दक्षिणपंथ को समझने में “फासीवाद” का परिभाषात्मक उपयोग खतरे से खाली नहीं है। इसका नतीजा आज की स्थिति की अतिरंजित ढंग से पेशकश ही नहीं, बल्कि हमारे वक्त की विशिष्टता और गंभीरता को कम करना भी हो जाता है।

आज के नव–उदारवादी दौर में फासीवादी प्रवृत्तियाँ पूंजीवादी व्यवस्था के राजनीतिक -आर्थिक संघटन में समाहित हो गई है। वर्गीय और अन्य विभाजनकारी भिन्नताएं राजकीय कार्यकलापों के स्तर पर, विशेषकर पूंजीवादी लोकतंत्र के तहत छिपी रहती थीं, जहां संप्रभुता को निर्वैयक्तिक कानूनी प्रणाली के माध्यम से काम करना होता था और जो सभी पर समान रूप से लागू होती थी। (गासपार मिकलोस तामास) जबकि इसके विपरीत, फासीवादी तानाशाही विभाजनकारी भिन्नताओं को उजागर कर उसी के आधार पर मनमानी नीतियों द्वारा संप्रभुता स्थापित करती थी — “संप्रभु वह है जो अपवाद पर निर्णय लेता है।”

1970 के मध्य से ही लगातार पूंजीवाद के नवोदारीकरण के दौर में पूंजीवादी राजसत्ता ने फासीवादी प्रवृत्ति को इस प्रकार से आत्मसात किया है कि पूंजीवादी जनतंत्र के तहत भी संप्रभुता का वही रूप हो गया है, जो खुले तौर पर मनमानी नीतियों द्वारा अपने विभाजनकारी चरित्र को पेश करता है — सार्विक नागरिकता के आदर्श की जगह पर नागरिकता को विशेषाधिकार और श्रेणीबद्ध बना देता है। दूसरी तरफ, आज फासीवादी भीड़ — संगठित/केंद्रित हो या असंगठित/विकेंद्रित हो दोनों ही रूपों में दैनिकता में लगातार विद्यमान रहती है। ये आज पूंजीवादी जनतंत्र के लिए खतरा नहीं है, बल्कि नवोदार पूंजीवादी जनतंत्र को पॉपुलिस्ट चरित्र देती है, और बदलती सरकारों को इसी के दायरे में काम करना होता है — विशेष प्रकार के लोकवृत्त का निर्माण करती है, जिसके तहत विचारधारात्मक रूप से भिन्न राजनीतियाँ आपस में प्रतिस्पर्धात्मक विनिमय संबंध बना पाती हैं, और एक दूसरे की पूरक बन जाती हैं। क्या यही आज भारत की दशा नहीं हो गई है? चाहे केंद्र सरकार हो या राज्य सरकारें हों, चाहे वह अति-दक्षिणपंथी भाजपा नेतृत्व की सरकार हो या किसी और पार्टी के नेतृत्व की सरकारें हों, चाहे शासक पार्टी हों या विपक्ष की पार्टियां हों, सभी इस भीड़ को भीड़ रूप में ही नियोजित करने की कौशिश कर रहीं हैं, चाहे कोई सांप्रदायिक आधार पर करे, या फिर भाषाई या अन्य आधारों पर। नव-उदारवादी संदर्भ में इस उत्तर-फासीवाद के खिलाफ संघर्ष किस प्रकार से ऐतिहासिक फासीवाद के खिलाफ लड़ाई के तौर-तरीकों से, जिसके लिए फासीवाद एक चिह्नित आंदोलन और राज्य था जिस पर सीधा निशाना साधा जा सकता था, लड़ा जा सकता है?

जैसा कि बार बार कहा गया है पूंजीवादी समाज में अलगाव और कुंठा स्वाभाविक है, जो कि समाज में फैलते सर्वहाराकरण, असमानता, व्यक्तिकरण और प्रतिस्पर्धा का सीधा नतीजा हैं। इस समाज का हर वर्ग इनसे प्रभावित होता है। एंगेल्स अपनी आरंभिक पुस्तक, द कन्डिशन ऑफ द वर्किंग क्लास इन इंग्लैंड (1845) में सामाजिक प्रतिस्पर्धा का बखूबी चित्र खींचते हैं:

“प्रतिस्पर्धा आधुनिक नागरिक समाज में सभी के विरुद्ध सभी की लड़ाई की पूर्ण अभिव्यक्ति है। यह लड़ाई, जीवन के लिए, अस्तित्व के लिए, हर चीज के लिए लड़ाई, जरूरत पड़ने पर जीवन और मृत्यु की लड़ाई, केवल समाज के विभिन्न वर्गों के बीच ही नहीं, बल्कि इन वर्गों के अलग-अलग सदस्यों के बीच भी लड़ी जाती है। हरेक आदमी दूसरे के रास्ते में है, और हरेक अपने रास्ते में आने वाले सभी लोगों को बाहर निकालने और खुद को उनकी जगह पर रखने का प्रयास करता है। मजदूर आपस में उसी प्रकार लगातार प्रतिस्पर्धा में रहते हैं, जैसे कि पूंजीपति वर्ग के सदस्य।”

यह “सभी के विरुद्ध सभी की लड़ाई” व्यक्तिगत और सामाजिक स्तर पर कुंठित आशाओं और मानसिक-भौतिक रुग्णताओं को पैदा करती है। इन कुंठित प्रवृत्तियों और रुग्णताओं को लेकर तीन तरह की राजनीति हो सकती है। एक, जो इन कुंठाओं को नियंत्रित और प्रबंधित करे ताकि वे व्यवस्था के लिए खतरा न बन जाएं, तथा प्रतिस्पर्धा को और तेज कर उसे पूंजीवाद के सामाजिक पुनरुत्पादन का जरिया बना दे; दूसरा, जो इन कुंठाओं के तह में जाए, और उसके आधार पर चोट करे; और तीसरा, वह जो कुंठा को ही राजनीति बना ले। पहले प्रकार की राजनीति के तहत सभी बुर्जुआ राजनीतिक शक्तियां — लेफ्ट-राइट-सेंटर, उदारवादी हों या रूढ़िवादी — होतीं है, दूसरे के तहत क्रांतिकारी अथवा परिवर्तनगामी राजनीति होती है जो व्यवस्था को ही चुनौती देती है। तीसरे में धुर-दक्षिणपंथी शक्तियाँ शामिल हैं जो कुंठितों की कुंठाओं की जैविक अभिव्यक्ति हैं — जो शिकायतों और लांछनों की भाषा में ही अभिव्यक्त होती हैं। यह बात फासीवादी या अन्य-धुरदक्षिणपंथी जन-आंदोलन के लिए तो सही ही है, जो राजनीतिक-आर्थिक संकट के दौर में राज्य की वैधता (legitimation) को अन्य दक्षिणपंथ और रूढ़िवादी शक्तियों के साथ जुड़ कर पुनर्स्थापित करने की कोशिश करता है। जिस प्रकार से पूंजीवाद की राजकीय-वैधानिक व्यवस्था औसत आदमी के रूप में सभी वर्ग के व्यक्तियों को ढालता है, उसी औसत आदमी की कुंठाओं को धुरदक्षिणपंथ एकत्र कर राजनीति का रूप देता है। क्रांतिकारी शक्तियों को इसी औसतीकरण के खिलाफ वर्गीय राजनीति को सामने रखना होगा। उदारवादी औसतीकरण का पूरक है फासीवादी औसतीकरण जो पूंजीवादी सामाजिक पुनरुत्पादन के संकट के दौर में सामने आता है।

हमने मोर्चा के पिछले अंक के संपादकीय में आज के दक्षिणपंथी उभार के कुछ कारणों पर ध्यान दिया था। संक्षेप में हम बोल सकते हैं कि नवोदार पूंजीवादी प्रक्रियाओं के तहत बेशीकरण, सर्वहाराकरण और प्रतिस्पर्धा में तेजी ने न्यूनीकृत राजसत्ताओं के लिए वैधता–संकट (legitimation crisis) पैदा कर दिया है। बेशी और सर्वहाराकृत आबादी की बढ़ती तादाद की आपसी प्रतिस्पर्धा ने पूंजीवाद की प्रतिस्पर्धात्मक राजनीतिक व्यवस्था को अनिश्चित बना दिया है। दक्षिणपंथी जन पार्टियों का ऐतिहासिक योगदान फासीवाद की तरह ही इस आबादी को इस रूप में संगठित करना होता है कि वे पूंजी के शासन के लिए खतरा न बन सकें। परन्तु 1920 – 45 के दौर में पूंजी, उसके मूर्त स्वरूप और बाजार राष्ट्रीय सीमाओं के आधार पर अपने आप को नियोजित करते थे और इसी कारण राष्ट्रीय नीतियों और राजनीतियों के आधार पर पूंजी संचय के राजनीतिक अर्थतांत्रिक मॉडलों की तैयारी हो सकती थी। लेकिन पूंजी के बढ़ते वित्तीयकरण और भूमंडलीकरण ने राज्य की इन क्षमताओं को कमजोर कर दिया है, और व्यवस्थापरक राजनीति की भूमिका आज जन असंतोष को व्यक्तिकृत और फिर उसे संगठित कर कुंद करना है, कोई सुव्यवस्थित राजनीतिक–आर्थिक मॉडल देना नहीं है। ऐसे में राजसत्ता-केंद्रित संघर्षों से हम किस हद तक आज के दक्षिणपंथी विकृत जन आंदोलनों की मौजूदगी से निजात पा सकेंगे?

हमारा मानना है कि पुराने संघर्षों से अभी भी बहुत कुछ सिखा जा सकता है, परन्तु उनको मॉडल की तरह इस्तेमाल करना गलत होगा – हम उनकी नकल नहीं कर सकते। हमें उनके प्रासंगिक गुणों को नया स्वरूप देना होगा। संघर्ष का स्वरूप हमेशा समय और स्थान से बंधा होता है। दूसरे समय या स्थान के संघर्षों से सीखने का अर्थ उनकी पुनरावृत्ति नहीं हो सकती। जिनके लिए वर्तमान महज पुनरावृत्ति है, वह अतीत की झूठी निश्चितताओं को जीना चाहते हैं। यहाँ हम संक्षेप में कुछ रणनीतिक सीख को सामने रखेंगे।

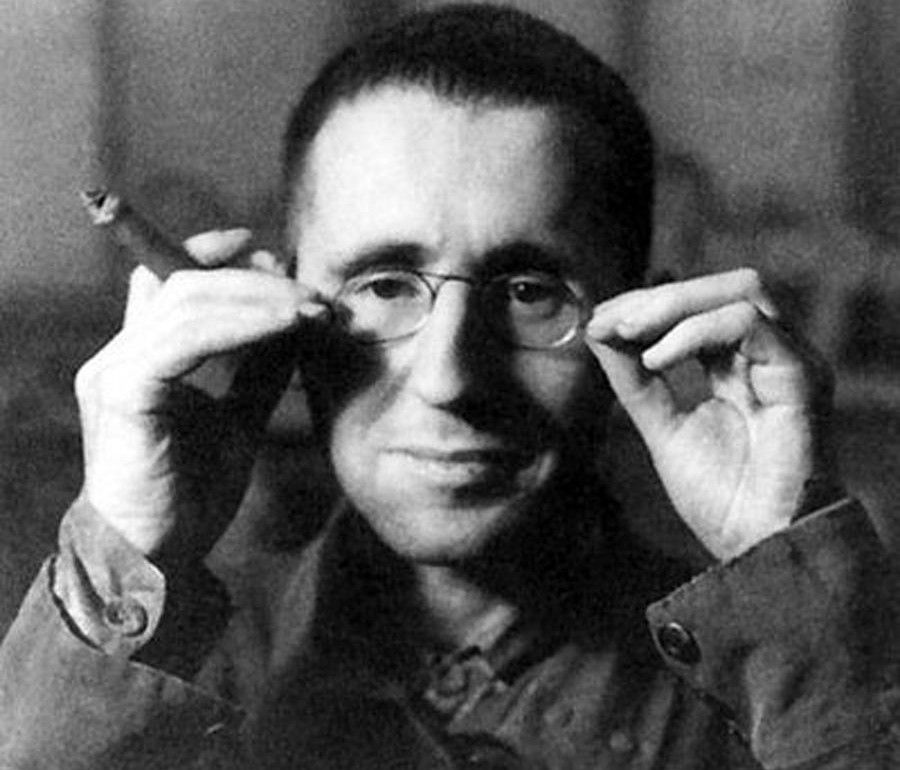

फासीवाद के विरोध का सबसे सुगठित जन-आंदोलनकारी स्वरूप कम्युनिस्ट इंटरनेशनल के व्यवहार में पैदा हुआ, जिसका आकार मार्क्सवादी इतिहासकार एरिक हॉब्सबॉम के अनुसार संकेंद्रीय वृत्त की तरह था। “श्रम की संयुक्त ताकतें (‘संयुक्त मोर्चा’ या यूनाइटेड फ्रन्ट) लोकतंत्रवादियों और उदारवादियों के साथ एक व्यापक चुनावी और राजनीतिक गठबंधन (‘लोकप्रिय मोर्चा’ या पोपुलर फ्रन्ट) की नींव रखेगी। इसके अलावा, जैसे-जैसे जर्मनी आगे बढ़ता गया, कम्युनिस्टों ने ‘राष्ट्रीय मोर्चे’ के रूप में और भी व्यापक विस्तार की कल्पना की, जिसमें सभी लोग शामिल थे, चाहे उनकी विचारधारा और राजनीतिक मान्यताएँ कुछ भी हों, लेकिन वे फासीवाद (या शक्तियों की धुरी) को प्राथमिक खतरा मानते थे।” इतिहासकारों का मानना है, चूंकि कम्युनिस्ट सिद्धांत और व्यवहार में भी अंतरराष्ट्रवादी थे, जिस कारण से फासीवाद के विरोध में राष्ट्रवादियों और देशप्रेमियों से ज्यादा दृढ़ प्रतिज्ञ ढंग से लोगों को एकत्र कर पाते थे। हॉब्सबॉम कम्युनिस्टों की फासीवाद-विरोधी रणनीतिक सक्षमता का आधार उनके व्यवहार की संरचना में देखते हैं।

“कम्युनिस्टों ने प्रतिरोध का रास्ता अपनाया, न केवल इसलिए कि लेनिन की ‘अग्रणी पार्टी’ की संरचना अनुशासित और निस्वार्थ कार्यकर्ताओं की एक ताकत तैयार करने के लिए बनाई गई थी, जिसका उद्देश्य कुशल कार्रवाई करना था, बल्कि इसलिए भी कि चरम स्थितियाँ, जैसे कि अवैधता, दमन और युद्ध, ठीक वही थीं जिनके लिए ‘पेशेवर क्रांतिकारियों’ के इन निकायों को बनाया गया था। वास्तव में, उन्होंने ही ‘केवल प्रतिरोध संघर्ष की संभावना को देखा था’…। इस मामले में वे जन समाजवादी पार्टियों से अलग थे, जिन्हें वैधता के अभाव में काम करना लगभग असंभव लगता था, चूंकि चुनाव, सार्वजनिक बैठकें और बाकी चीजें उनकी गतिविधियों को परिभाषित और निर्धारित करती थीं।” (एरिक हॉब्सबॉम, ‘दी एज ऑफ एक्सट्रीम्स’)

“श्रम की संयुक्त ताकत” के रूप में संयुक्त मोर्चा को समझना, राष्ट्रवाद के खिलाफ अंतरराष्ट्रवादी प्रतिबद्धता और चरम स्थितियों में काम करने योग्य सांगठनिक क्षमता — ये तीन सिद्धांत आज भी प्रतिक्रियावाद के खिलाफ संघर्ष में अहम होंगे। इन्हीं के आधार पर आज के संघर्ष की तैयारी हो सकती है।

प्रत्यूष चन्द्र